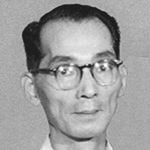

Legend 09: Design illustrates culture, Shozo Sato

Shozo Sato

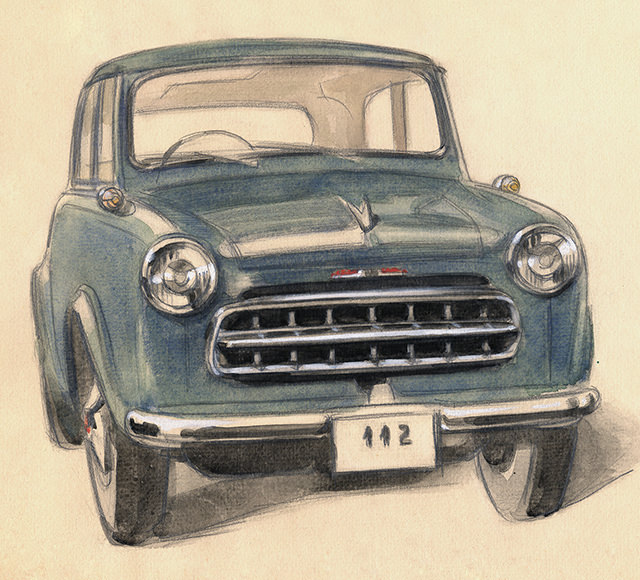

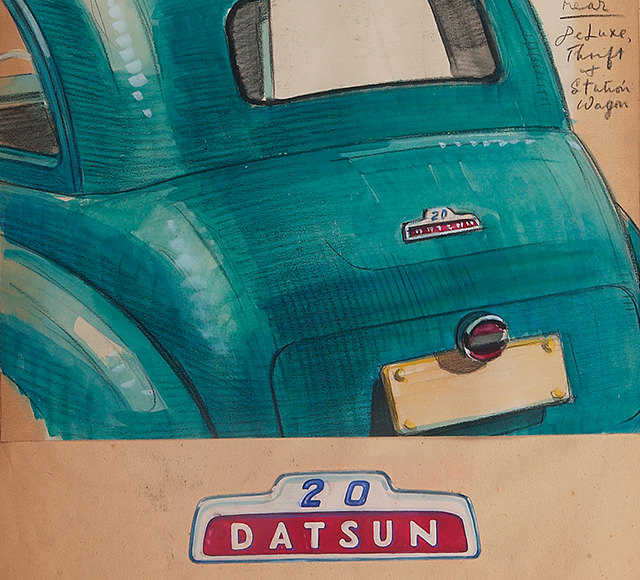

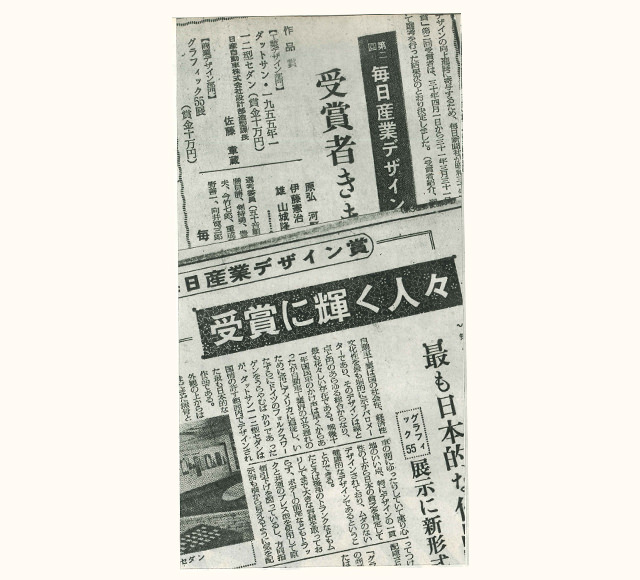

Shozo Sato joined Nissan Motor in 1937 and was transferred to the Design Department in 1948. He was appointed the head of the Body Design Team in 1950 and became the first head of the Design Department in 1954. It is believed that the first Bluebird (the 310 model) was based on his sketch. The Datsun Sedan 112 that he designed won the 1956 Mainichi Design Award in the industrial category, an award that the Mainichi newspaper established in 1955 to improve industrial design in Japan. Sato left Nissan Motor for health reasons in 1959.

To do the job right

Story

teller:

Isao

Sano

Isao

Sano

was

assigned

to

Nissan

Motor’s

newly

established

Design

Department

and

it

was

there

that

he

met

Shozo

Sato,

who

was

his

boss

and

also

the

person

with

overall

responsibility

for

design

work

at

the

automaker

in

that

period.

Imitatio Cecili was the author of a popular monthly column called “Reports on Vintage Cars” that appeared in Car Graphic magazine during the 1960s and introduced cars of the 1920s with beautiful watercolour illustrations. In fact, however, Cecili was the pen name of Shozo Sato, who had to write under a pseudonym because he had recently been an employee of Nissan Motor, where he had served as the head of the Design Department.

‘His design sketches were all done in watercolours and every one of them was just amazing. You could see the multiple facets of the structure in three dimensions,’ recalled Isao Sano, whom we interviewed to ask about Sato.

Sato’s

sketch

of

the

Datsun

112

using

the

watercolour

technique

*Watercolour

technique

involves

painting

on

Watson

Paper

using

watercolours.

Sato

excelled

at

this

technique.

The Datsun 112

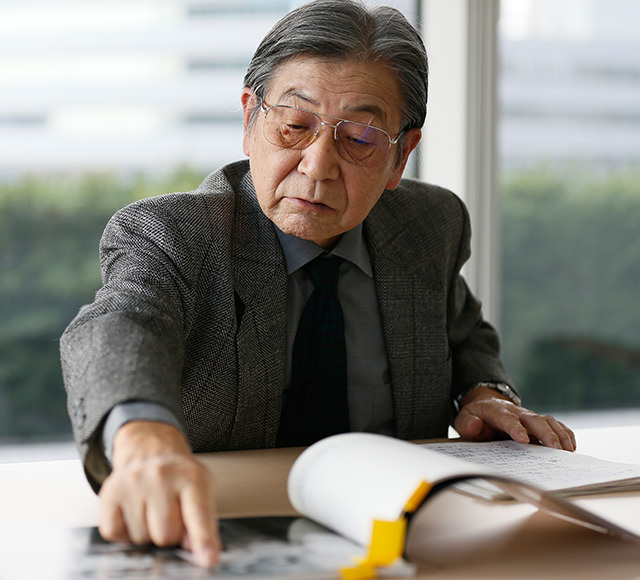

Sano was born in Tokyo in May 1932 and joined Nissan Motor in 1955 upon graduating from the Tokyo University of the Arts. He met Shozo Sato for the first time when he was still a university student.

‘In 1955, it was unusually difficult to get a job. This was the so-called employment ice age in Japan and most companies were not hiring new graduates. However, Nissan needed to add two people and I was one of them. Mr Sato took the trouble to travel all the way to my university in Ueno, Tokyo, to see me,’ he said, remembering his first impression of Shozo Sato.

‘I was interested in designing ships at the time and had worked as a trainee at Mitsubishi Shipyard during my third year at university. One of my university instructors recommended me to Mr Sato, because he knew that I had often said I wanted to design ships and he thought that working at a carmaker would be acceptable for me because both ships and cars were things that moved. I remember explaining to Mr. Sato about my drawings even though I can’t recall just what they were. I went through a couple of interviews with Nissan and then received an offer letter. After that Mr Sato contacted me and asked me to start at the company right away. So I was working there about once a week before I officially joined the company.’

Mr. Sano gave interview.

What is required of a designer

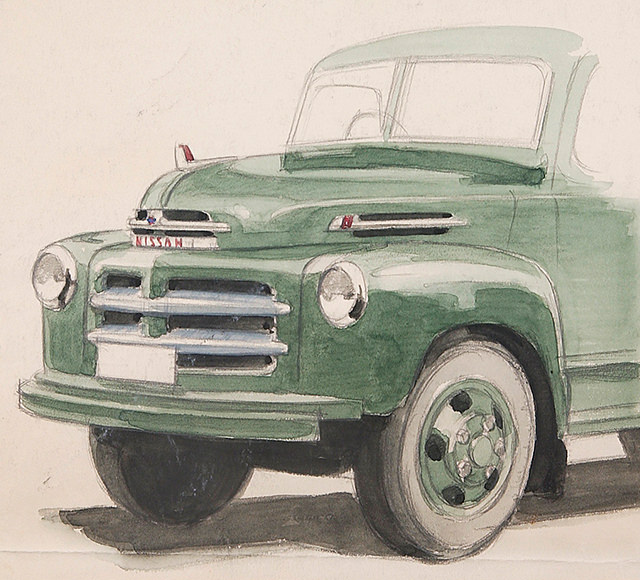

Sketch of the Nissan 480 truck (introduced in 1953).

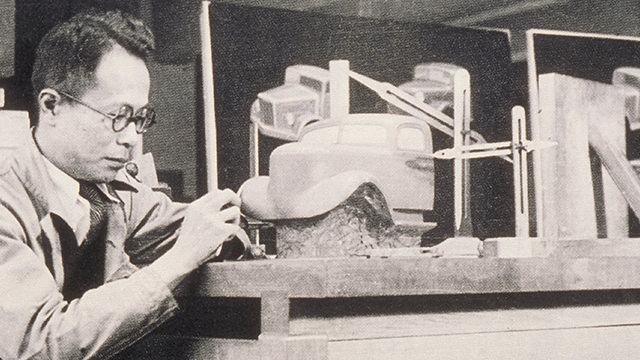

One day, Sato ordered Sano to ‘draw a copy of the chassis layout of this sports car.’ With hardly any knowledge of automobiles, it proved to be a tedious job for Sano but he finished the drawing. Then Sato ordered him to put body panels on the drawing he had just made.

‘Mr Sato took time to explain in detail how a car is made by going over each and every part of the chassis layout with me,…pointing out that this was the suspension and this was the transmission…. At the time I felt bad because I thought it must have been a major problem for him to teach such basic things to a young man who had just joined a car company with no practical knowledge of cars. However, it is essential for a designer to understand the structure and layout of a car. A designer who doesn’t have that knowledge can’t design a car that not only looks good but also works as a package. It was only after some time that I realised that this must have been the concept that Mr Sato was trying to teach me.’

The Design Department that Sano was assigned to eventually become the Global Design Center but at the time it was only a year old. Before the creation of the section, there were ‘modellers’, but their job related to only part of the body design process. In fact, there was no term for the job that came to be the province of designers. In those days, carmakers designed engines and chassis, but they outsourced the majority of the bodywork, which was a general design method. However, as demand for cars gradually increased, automakers began to believe that it would be more efficient to employ an integrated process that started with design and extended to manufacturing and included the car bodies. Nissan responded to this need by creating the Design Department, an independent section that specialised in designing the bodies of the company’s motor vehicles.

Coloured pencil sketch of the Nissan Junior (introduced in 1956).

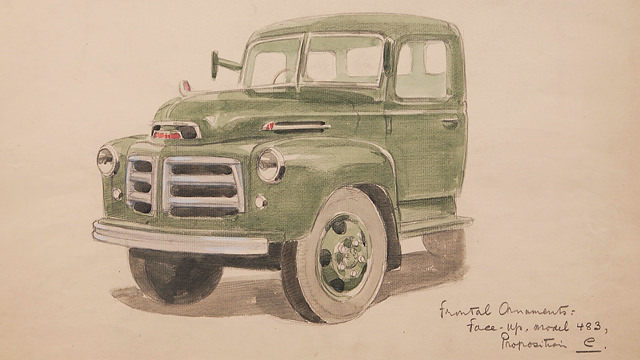

Sketch of the Nissan 483 truck.

‘I

didn’t

even

have

a

driver’s

licence

when

I

joined

Nissan.

The

Design

Department

had

test

vehicles

that

the

engineers

used,

for

example

for

commuting

and

for

testing,

and

to

get

practice

behind

the

wheel

I

drove

those

cars

while

they

were

in

the

garage

for

maintenance.

I

didn’t

even

know

how

cars

were

made

at

the

time,

but

actually

driving

myself

stirred

my

interest

in

automobiles.’

How

did

Sano

see

Shozo

Sato

as

a

man

when

he

started

to

work

with

him?

‘In modelling, he was a strongman who was involved in everything. It wasn’t that he didn’t trust his subordinates. I believe it came from his sense of responsibility for the work. He must have felt that he wanted to have, or that he had a responsibility to have, a thorough understanding of everything in detail whenever he was engaged in the creation of anything,’ said Sano.

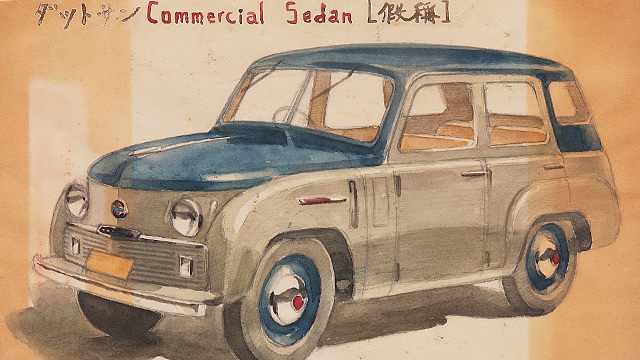

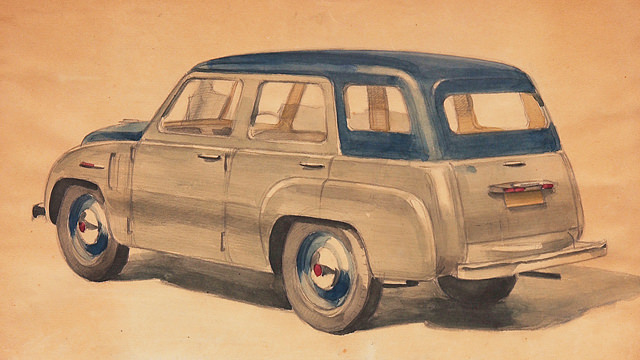

Sketches of the Datsun commercial sedan.

Naturally, and quite rightly, Sato could be very strict with his subordinates. ‘He scolded me often,’ Sano recalled. ‘But he was not the kind of person who would go into a rage. He recognised when something was done right, even if a subordinate had done the job. I remember when I was working on making a quarter-size clay model from a sketch of his, but his sketch wasn’t really three dimensional, so I went and told him about it. He didn’t say anything. He just nodded and accepted the criticism. He wouldn’t get angry over nothing; when he became angry, there was a reason. And when he saw something, he would address it regardless of who the person was.’

Sketch of the Datsun 20.

The Design department started in 1954 with only eight employees (Sato is the third from the left). The moment when ‘Nissan Design’ was born.

The ones who tended to bear the brunt of his anger were not the people who worked under him in the Design Department but rather people who were outside the section. Sato was known to be very frank and speak his mind at meetings of section and department heads and this reflected his very clear concept of what car design was and his strong commitment to the concept.

Established the foundation of Nissan design

Sano recalls Shozo Sato as a tall, slender man who was a bit of a dandy and almost looked more like an engineer than a designer, but he was not quite like an ordinary engineer, either. ‘Engineers tend to consider a car a piece of machinery. Their concerns revolve around the target features and performance of the car. In contrast, Mr Sato had a vision of life with a car and a culture nurtured with cars.’

In a company that manufactured cars and tended to focus on features and performance, Shozo Sato often demonstrated his anger with people outside his section when it came to the subject of making cars.

‘He was a heavy smoker and there were stacks of empty cigarette boxes on his desk. And he looked so cool with a cigarette hanging out of the corner of his mouth,’ Sano laughed. ‘He also loved smoking a pipe. One day Mr Sato returned to his desk from the regular meeting of department and section heads in a bad mood and we figured that things must have gone badly at the meeting. He said that he’d been clenching his fists so tightly that he thought his fingernails would be drawing blood from his palms and because he was caught up in his emotions, he stuffed too much tobacco into his pipe, so it wouldn’t light. I think that he must have been speaking out for what he believed in at those meetings, so that the Design Department could do the job right and so that the right work would be approved as such.’

Mr. Sano gave interview.

Modelling

Technique

Clay

modelling

is

said

to

have

started

in

the

US

in

1919,

when

water-based

clay

was

used

for

modelling.

The

idea

was

groundbreaking

because

clay

made

it

possible

to

make

multiple

corrections

easily,

as

opposed

to

the

wood

modelling

generally

used

up

until

then.

Shozo Sato might have had a very strong will, but in fact he was not so strong physically and he was forced to take sick leave more than once.

‘Even when he stayed home for health reasons, he was always thinking about work. At one point in time he lived in the Ofuna area in Kanagawa Prefecture and there was a Nissan chassis designer who lived in the same neighbourhood. When Mr Sato was home sick, almost every day he would write a memo about work, jotting down his thoughts, and give it to this designer to deliver to us. We would read it, work out our response, and then go see him at his house right away. But before we actually went up and knocked on his door, we’d go into a coffee shop and have an ad hoc strategy meeting, saying things like “We should talk about good things first, so he’ll think we’re doing a good job,” and “Let’s leave the bad news that might make him scold us until later” (laughter). We called this “the Ofuna courier run”.’

Shozo Sato was not only equipped with a strong sense of responsibility and high standards regarding work. He also had some personal magnetism. ‘One day out of the blue he said he was going to do an oil painting of an Austin A50 and he put an easel next to his desk. The oil paint had a strong smell and it was unpleasant for those of us working nearby,’ recalled Sano with laughed. ‘Also, his desk was covered with stacks of documents and he left them there so long that their colours faded. He wouldn’t do so-called desk work as a section head, but he couldn’t care less and he would say with a smile things like, “I’ve heard that I’m the worst-performing section head in the entire company. I wonder if it’s true.” He was a likeable chap. He just had that something that made people like him and care about him.’

Working in the Ogikubo Model Room in Tokyo sometime between 1955 and 1965.

Be responsible for culture

1/5-scale oil-clay modbased el of the Datsun 110.

So what kind of designer was Shozo Sato? Was he a designer who came up with unique ideas based on extraordinary techniques? Sano replied, ‘Mr Sato’s designs were extremely simple. He modelled with natural curves of planes and turned them into sophisticated designs with thought-out detail. He demanded a coherent design that naturally created two planes on drawing one single line. He didn’t like designs that were half sharp or half perfect. He used to tell us to think of the structure. He must have meant to understand a car in three dimensions and design it in a way that would not destroy the harmony anywhere.’

At the time, the design of American cars was the mainstream in the world, as the embodiment of the American dream. Its influence was such that even Mercedes-Benz adopted tail fins. Sano testified to this trend, saying, ‘Certainly there was a trend that all carmakers had to reflect the latest fashions of the time. However, this was incompatible with Mr Sato’s concept. Right to the end, he adhered to his pure and simple design approach. As a result, he won the Mainichi Design Award in 1956. His design was accepted and recognised in Japan.

Articles on the winning of the Mainichi Design Award.

‘During that period something else was troubling Mr Sato. He was in search of consistency between the design he believed in and the design that the target buyers of cars or the majority of consumers desired. This is, of course, an eternal challenge for designers.’

Sano recalls what Sato used to say all the time: ‘Think about how you can take responsibility for culture. Culture is the integrality of the proof that you are living, of how you want to live your life, of what kind of dreams you have. And what happens when you put a car into this process is that it can be interpreted as wishes, people’s wish to drive certain cars, or their wish to live with other types of cars. Design with consideration for these thoughts and dreams of people. Don’t put corporate convenience or logic at the centre of your design, but don’t ignore them completely either. That is the work of a professional designer. I believe that was the message that Mr Sato wanted to convey.’

Shozo Sato created the foundation of Nissan design. Sano was a direct disciple of Shozo Sato and concluded our interview by expressing his hope that Nissan would continue to adhere to Sato’s ideas into the future.

Profile of the writer

Isao

Sano

Isao

Sano

was

born

in

Tokyo

in

May

1932.

He

joined

Nissan

Motor

following

his

graduation

from

the

Tokyo

University

of

the

Arts

in

1955.

After

he

retired

from

Nissan

in

1987,

he

served

as

the

president

of

Creative

Box,

a

Tokyo

company

created

as

a

satellite

design

studio

base

for

Nissan.

After

he

left

Creative

Box,

he

founded

the

Katachi-no

Kai,

a

social

association

for

people

who

had

once

worked

in

Nissan’s

design

department.

Sano

says

of

his

reason

for

organizing

the

association,

‘I’m

not

someone

who

believes

in

fate,

but

it

was

by

chance

that

we

all

ended

up

working

in

the

Design

Department

of

Nissan.

I

wanted

to

create

a

sort

of

friendly

gathering

place.’

It

consists

of

informal

groups

that

meet

under

such

themes

such

as

golf,

painting,

and

pottery.

It

is

also

largely

responsible

for

the

creation

of

Nissan’s

design

archives.