Legend 03: The man who found his calling, Hiroyoshi Kato

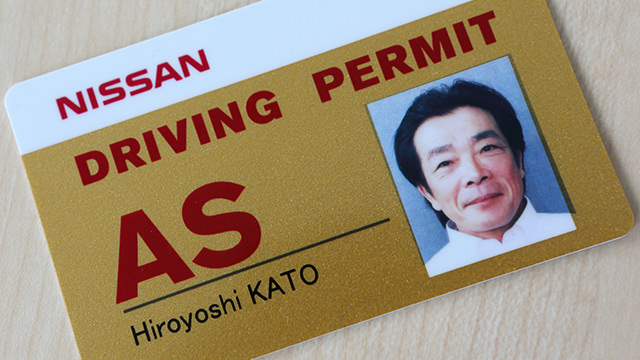

Hiroyoshi Kato

Born 5 September 1957 in Akita Prefecture. After he finished middle school, he entered Nissan Industrial Vocational School (now Nissan Automobile Technical College) and then went on to join Nissan Motor in 1976. He was assigned to Vehicle Test Section 3 of Vehicle Test Department 1, where he worked with the Cedric (330) team before being assigned to the Fairlady Z (S130) team.

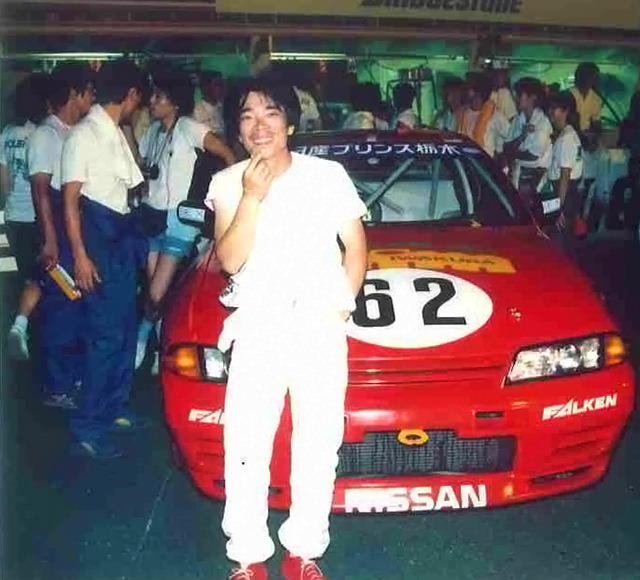

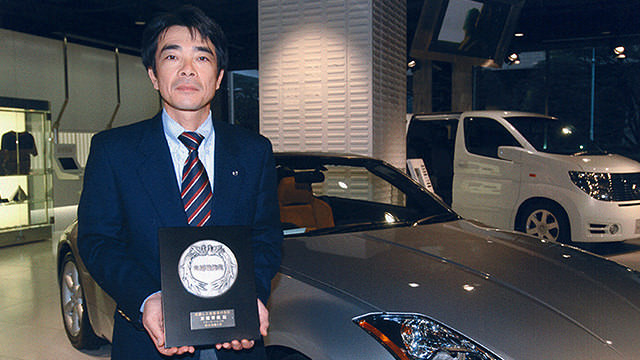

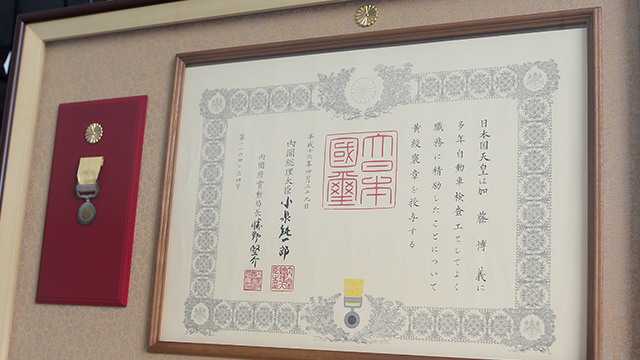

In 1988, he joined the GT-R (R32) team in Chassis Test Section 3 of the Chassis Test Department. In 1993, he was assigned to Dynamics Performance Test Section 1 of Product Test Department 1, where he was involved in the development of the GT-R (R33, R34), the Skyline (V35), the Fairlady Z (Z33), and other cars. In 2008, Kato became a technical meister of the Vehicle Test Department and since then he has been responsible for the overall dynamics performance of Nissan and Infiniti vehicles. He was named a ‘Contemporary Master Craftsman’ by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare in 2003 and awarded the Medal with Yellow Ribbon in 2004.

No licence

Black Test Car is a best-selling novel that was written by novelist and journalist Toshiyuki Kajiyama. It depicted cut-throat competition among car manufacturers and became so popular that it was made into a film. Hiroyoshi Kato, technical meister in the Vehicle Test Department of Nissan Motor and the focus of this issue, read the book when he was in primary school and in the process discovered his true vocation.

‘I’d always loved cars and like all the other boys who loved cars at that time, I wanted to become a race car driver. But my parents didn’t like the idea, telling me that “driving a race car is too dangerous”,’ recalled Kato with a laugh. ‘Then I happened to read this novel and the words “test car” sounded fresh and new and I discovered that there was in fact a profession called test driver. It’s a dream job: you get to drive cars just like a race car driver and you get paid for it! My parents were willing to accept this idea because they seemed to think that it wasn’t likely to be dangerous, because no automaker would give their employees dangerous work.’

‘But

there

was

one

problem.

I

was

only

17

years

old

and

thus

too

young

to

have

a

driver’s

licence,

even

though

I

wanted

to

become

a

test

driver,’

he

told

us

with

a

laugh.

‘There

was

another

fellow

who

joined

the

company

in

the

same

year

as

I

did

and

he

and

I

are

the

only

people

in

the

history

of

the

company

to

ever

be

assigned

to

the

Vehicle

Test

Department

without

holding

a

driver’s

licence,’

recalled

Kato.

He

was

counting

the

days

until

his

18th

birthday

and

when

the

big

day

finally

arrived,

he

took

the

application

form

for

a

driving

school

to

his

superior

to

obtain

the

latter’s

signature

as

a

guarantor.

To

Kato’s

chagrin,

his

boss

had

a

totally

unexpected

reaction

to

this

request.

‘You

want

to

become

a

test

driver

who

helps

us

produce

cars

for

customers

to

enjoy

and

you’re

telling

me

that

you

are

going

to

be

taught

how

to

drive

by

a

mere

amateur?’

The first hurdle

Once he’d finally obtained his boss’s permission to drive, Kato constantly practiced driving so that he could pass the test for his licence. He made his own training ground in a corner of the test track facility, marking out an intersection and making traffic signs by hand. At the same time, he had more and more opportunities to experience the actual work of a test driver, for example by riding along with a test driver on endurance tests.

When Kato finally got his long-dreamed-of driver’s licence, he was assigned to the Cedric Development Team, but he promptly asked to be moved to the Fairlady Z team. ‘I joined Nissan because I was so inspired by the Z.’ Once again his passion touched his superiors and he was moved to the Z Development Team within a year. In the meantime, all he did was drive.

‘I drove anytime, anywhere. My superiors told me to improve my driving technique. I didn’t know what to do or how to do it, so I just drove. There was a test car that was no longer used, so I drove it during my lunch breaks, after work, and anytime I had free time. Of course, I was a terrible driver. In the end, my senior colleagues took pity on me and finally started to teach me how to drive. I’m talking about professional test drivers who worked on the front lines. I would say it was a very special education (laughter). One of them got in the passenger seat and put some documents on the fascia and told me to drive without making the documents move. When I drove, the documents fell down, but when he drove, they stayed in place the whole time he was driving. I hate to lose and I couldn’t stand that I couldn’t do what he could.’

Because Kato had never been taught at a driving school and had not really driven much privately, he hadn’t developed any particular habits when driving and as a result, he was able to absorb an enormous amount of the knowledge and techniques required for a test driver very rapidly, like a sponge soaking up water.

‘I never thought it was hard or wanted to quit, not even once. Because I got to drive cars that I loved and do so as much as I wanted. I was being taught by professionals among professionals. I didn’t have to pay for cars, tyres, or petrol. In addition, I received pay on the 25th of every month. Sometimes I got compliments for my driving from my seniors and then I felt like I was on top of the world (laughter).’

At this point, Kato suddenly seemed to remember something. ‘No, I take it back. It’s not true to say that I never felt like I wanted to quit. Only once, I thought that maybe I wouldn’t be good enough to do the job.’ His jovial expression seemed to turn sour all of a sudden.

Polish cars and myself

Looking

back

at

the

episode,

Kato

noted

that

even

if

he

could

have

driven

the

track,

he

didn’t

have

any

confidence

in

his

ability

to

complete

the

drive

with

the

car

unscathed.

In

fact,

even

a

more

experienced

driver

proved

unable

to

return

with

the

GT-R

unharmed.

‘On

the

first

lap

I

was

in

the

front

passenger

seat.

I

kept

watching

the

gauges

because

I

had

nothing

else

to

do.

Before

we’d

even

reached

the

halfway

point

of

the

circuit,

I

noticed

that

the

oil

temperature

exceeded

130

degrees

Celsius.

Our

experience

had

already

demonstrated

that

this

not

sustainable,

so

I

immediately

told

the

driver

to

slow

down.

If

we

had

continued,

we

would

have

blown

the

engine.

In

other

words,

we

could

not

even

finish

the

first

lap

normally.’

Back

in

the

pits,

a

total

of

around

20

engineers

surrounded

the

car

and

started

to

work

on

identifying

the

problems

and

figuring

out

how

to

solve

them.

‘At

that

point

a

Porsche

came

into

the

pits.

A

driver

in

a

short-sleeved

shirt

got

out

of

the

car

and

lit

up

a

cigarette,

then

walked

around

the

car

checking

the

condition

of

the

tyres

as

he

smoked.

When

he

finished

his

cigarette,

he

got

back

into

the

car

and

drove

back

out

on

the

track.

He

looked

overwhelmingly

cool

to

me.

And

what

were

we

doing?

We

were

driving

like

it

was

a

life

or

death

situation,

kitted

out

in

racing

suits,

and

still

the

vehicle

was

damaged

and

everybody

was

saying

what

was

wrong

and

what

was

right.

I

promised

myself

that

one

day

we

would

make

our

cars

like

that

car

and

I

would

be

like

that

guy.

That

scene

often

appears

in

my

dreams,

but

in

the

dream

the

Porsche

has

turned

into

a

Nissan

and

the

face

of

the

European

driver

into

me

(laughter).’

Cars should please the entire family

Once the R32 Skyline GT-R was launched, Kato was assigned to the R33 development team. At the same time, he participated in the Group N1 Endurance races (now Super Endurance) to improve his driving skills. He increased his experience and steadily achieved results. The more frequent his visits to Nürburgring became, the more laps he became able to drive.

Generally speaking, when going into a curve, a driver slows down by pressing the brake pedal, applies load to the front of the car, turns the wheel, and takes the curve. In fact, a car will negotiate a curve without decelerating that much or without the wheel being turned that much. However, when I wanted to do that at Nürburgring, it puts phenomenal pressure on me. If it was raining, it was so awful that my body was completely rigid with tension. Then I tried to hold the steering wheel with only three fingers and I found that I could go into the curve very smoothly. If you hold the wheel with all five fingers, sometimes you steer too late or too much. Steering with three fingers, I could make subtle adjustments, as if I were slightly pushing back the sidewall distortion of the tyres.’

That was the moment when the three-finger driving technique—his unique driving style—was born. Now Kato knows not only the course marshal at Nürburgring but also the test drivers of Porsche and other carmakers. He has become known as an undisputed, first-class test driver.

Kato often speaks of ‘everyday use.’ When he does, he’s referring to the general customer driving a car daily and addressing this situation is his top priority for every car development project.

‘I wear this Tudor Chrono-Time watch every day. One day I was scolded by someone who said that I shouldn’t be wearing such a valuable watch every day. They said I should only take it out for special occasions in order to take better care of it. But this is a watch that I’d wanted for a long time and then finally bought, so I want to wear it all the time. I think a sports car, for example, is the same. If a customer has finally bought the sports car he has always dreamed of but thinks that it would be too showy to drive it to a convenience store or if he doesn’t like to drive it on rainy days, it’s such a waste. Also, when I see a sports car on the street, the driver looks happy but sometimes the front seat passenger looks unhappy. If a car fails to please your partner or your family, there’s no point in owning it. Automakers should produce cars that will make the rest of the family feel good about the purchase when the father goes out and buys one.’

The man who made his own dream come true is developing cars with all his heart and soul so that the cars customers dream of don’t remain only dreams.

Profile of the writer

Shintaro

Watanabe

Born

in

1966

in

Tokyo.

After

graduating

from

a

university

in

the

US,

he

worked

as

an

editor

of

Le

Volant,

an

automobile

magazine,

before

joining

Car

Graphic’s

editorial

staff

in

1998.

He

left

Car

Graphic

in

2003

and

became

a

representative

of

MPI,

an

editorial

production

company,

while

also

working

as

an

automotive

journalist.

He

also

works

as

a

chief

editor

for

Car

Graphic.