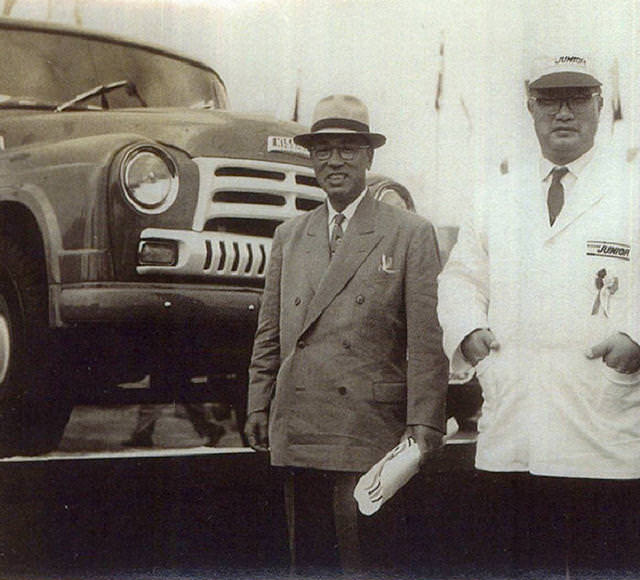

Legend 02: A determined visionary, Yutaka Katayama

Yutaka Katayama

Born in September 1909, in Harunocho, Shuchi-gun (now Hamamatsu City), Shizuoka Prefecture.He went to the US for the first time as an assistant on a high-speed vessel carrying raw silk to the US in 1927, while he was a student at Keio University. This first-hand experience of how America worked was an advantage in his later business career. He joined Nissan Motor in 1935 and was assigned to the Administration Department, where he worked in publicity and advertising.

He

proposed

an

ad

that

focused

on

the

customer’s

lifestyle

with

a

car,

drawing

a

line

from

the

conventional

advertising

of

the

day

that

loudly

repeated

the

car’s

name

over

and

over.

Katayama

was

successful

in

communicating

Nissan

and

its

products

in

a

smart

manner

by

featuring

representative

celebrities

of

the

time

in

the

company’s

TV

advertising

and

collaborating

with

other

industries,

which

was

an

innovative

technique

at

the

time.

He

also

promoted

the

first

All-Japan

Motor

Show

in

1954,

in

anticipation

of

the

emerging

era

of

motorisation

in

Japan

and

so

that

the

entire

industry

could

make

a

statement

to

the

world.

All

of

the

country’s

automakers

participated

and

the

show

was

a

huge

success,

attracting

over

half

a

million

visitors.

With

the

company

looking

ahead

to

the

full-scale

export

of

Datsun

cars,

he

was

team

manager

as

two

Datsun

210s

were

entered

in

a

gruelling

rally

circumnavigating

the

Australian

continent.

Nissan

snared

the

honour

of

a

class

victory,

instantly

catapulting

the

brand

into

worldwide

renown.

In

1960,

Katayama

started

building

the

foundations

of

Nissan

North

America,

working

from

a

base

in

Los

Angeles.

In

the

meantime,

he

put

together

the

key

concepts

for

the

Z-car,

a

model

that

made

it

possible

for

everyone

to

enjoy

fast,

agile

driving,

thereby

contributing

significantly

to

the

birth

of

an

exceptional

sports

car.

In

1998,

he

was

inducted

into

the

Automotive

Hall

of

Fame

in

Dearborn,

Michigan,

with

his

citation

declaring

that

‘he

accomplished

numerous

great

achievements

in

the

USA,

where

motorisation

is

highly

advanced,

because

of

his

strong

passion

for

automobiles,

long-term

management

perspective,

and

diverse

experiences,

and,

above

all,

because

of

his

integrity—he

loved,

understood,

and

unstintingly

cooperated

with

and

supported

people

regardless

of

nationality,

ignoring

borders.’

He

is

a

great

figure

in

the

automotive

industry

of

whom

Japan

should

be

very

proud.

Still

giving

interviews

at

the

astonishing

age

of

104,

he

mentioned

that

his

favourite

food

was

steak,

and

that

he

would

regularly

drink

two

to

three

litres

of

water

a

day,

declaring

that

‘water

is

my

medicine.’

He

passed

away

on

19

February

2015,

at

the

age

of

105.

Origins lie in sense of exhilaration

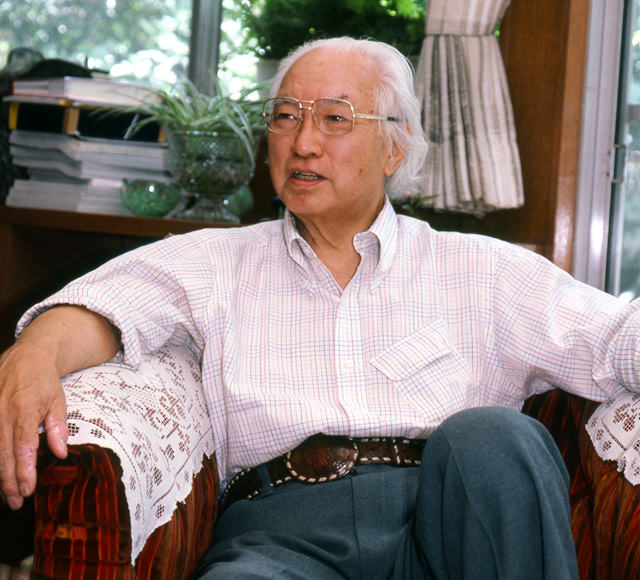

Yutaka Katayama, also known as Mr. K, will celebrate his 105th birthday in September 2014. With a beaming smile and charming poise, he made us burst into laughter and sometimes made us stop and think as he mischievously related a string of episodes from his long and illustrious life, making us completely forget that the old man in front of us was a ‘historic’ person born in the same year as jazz greats Gene Krupa and Benny Goodman. The person in front of us seemed to be simply a boy who loved cars. His freshness, sensitivity, and youthful spirit must be why Katayama has always remained Mr K instead of becoming a venerable elder with a famous name who has made it to the age of 104.

I was very surprised to learn that for Katayama, ‘something to ride’ was in the beginning a horse. ‘My father loved horses and every morning before he went to work he would go for a ride on his horse,’ recalled Katayama. ‘We were living in Tomakomai in Hokkaido at the time and he galloped along the water’s edge at the beach. I sat in front of him and, how can I express that feeling, it was a pure jubilation that cannot be expressed in words, a vitality that invigorates you from head to toe.’

Mr. Katayama in childhood, with parents and his aunt.

The ornament of a horse putting in his office.

From the time that he started to work for Nissan Motor in 1935, he always kept searching for the ideal relationship between human and car and it was fascinating to discover that his sense of that ideal was rooted in his original experience of the relationship between man and horse when he still a young boy.

‘Of course, horses have not only provided humans with pleasure. We also owe them a huge amount because of all that they have done for us over the course of 5,000 years. Automobiles were devised as a potential replacement for horses, but it has only been 100 years since they were commercialised and the unfortunate truth is that we have not been successful at producing cars that can completely replace horses. I know this all too well because I lived close to horses when I was a child. A horse makes itself to go in the direction in which the rider wishes to go and it can return on its own when the rider has dismounted. However, it would be hasty to conclude that all we have to do is “make an automatic car that moves on its own”,’ Katayama exclaimed.

Insisting on keeping it simple

He went on to explain his thinking more fully. ‘After all, horses have to be controlled by humans. The rider needs to bring out the horse’s best and compensate for its weaknesses. Cars are the same. They become good cars if drivers handle them well. As a result, a driver can experience a sense of jubilation beyond all reason, sort of like adding one and one to get not two but, say, five or 10, which is the joy of driving a car that a driver can only feel if he and the car become like one. In any event, we’re not selling empty bodies called cars. Rather, we sell “driving performance” or “a driving experience”. We earn money by offering this driving experience to our customers. That’s why I persist in valuing the well-spring that is the driving experience.

‘In

any

case,

even

though

we

have

been

disciplined

and

focused

and

have

worked

hard,

it

has

been

very

difficult

to

create

something

that

truly

can

replace

a

horse.

People

are

now

talking

about

new

features

for

cars,

like

automatic

collision

avoidance

systems

and

devices

to

wake

up

drowsy

drivers.

A

horse

may

not

wake

you

up,

but

it

will

stop

on

its

own

if

it’s

approaching

danger.

That’s

because

the

rider

is

paying

attention

and

the

horse

senses

the

rider’s

wishes

and

perceives

the

situation

correctly.

That’s

why

horses

were

appreciated

so

much

during

the

days

of

the

cowboys

and

their

horses

in

the

US.

I

went

to

the

US

for

the

first

time

85

years

ago,

while

I

was

still

a

student,

and

in

those

days

horses

were

still

used

in

a

wide

range

of

daily

activities

by

the

American

people.

Automobiles

were

still

playing

the

role

of

supplementing

horses

back

then.’

Reflections

such

as

these,

which

dated

back

to

Katayama’s

childhood,

ultimately

changed

form

and

led

to

the

birth

of

‘that

sports

car’

that

we

all

know

so

well.

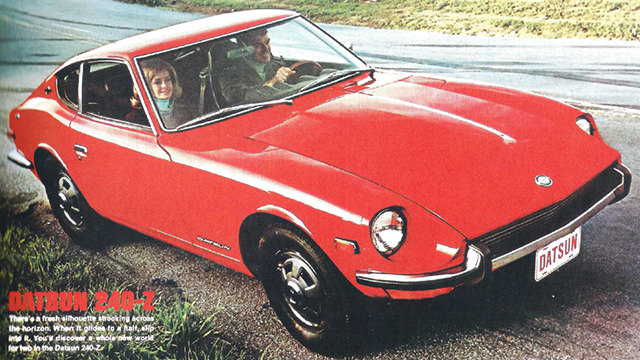

‘How can we transpose the relationship between man and horse into the one between man and car? Even after I was sent to Los Angeles in 1960 to establish Nissan Motor in the US, this question never really left me. Eventually I came up with the concept of the Z-car. It was a sports car with a sleek body with a long nose and a short deck, designed so that it could be built utilizing some of the parts and components that were already used in our other production cars, and it was a car that anybody could drive easily and that would give the driver that incredible feeling of jubilation that comes when car and driver are as one. Fortunately, it became a big hit and we were soon turning out 4,000 units a month. Then we began to deploy dedicated production lines to keep up with demand. I personally think that our success reflected our ability to capture something of the relationship between man and horse and that the purity and simplicity of this concept touched the hearts and spirits of our customers.

Doctors and medicine

Katayama tends to be in the spotlight because of his reputation as ‘the father of the Z-car’, but he became well known as a man of innovative ideas immediately after he joined Nissan Motor. ‘To be honest, I wanted to study engineering at Tokyo University and then go into car manufacturing, but this dream never came true (laughter). Instead, I graduated from Keio University and joined Nissan, where I was assigned to the Administration Department and was responsible for publicity and advertising. But I’m grateful now because this experience taught me a lot.’

Here are some examples that showcase his ideas. In advertising for Datsun cars, he featured Takiko Mizunoe, an extremely popular actress who typically played the part of a male on stage in a regular revue and was so beautiful that she was nicknamed the ‘fair lady in men’s attire’. Katayama stunned the audience when he introduced 10 Datsun cars with Takiko Mizunoe on the stage of the Shochiku Girls Revue Company at the height of the latter’s popularity in 1935. In another move, he masterminded the adoption of Nissan vans by Mitsukoshi Department Store for the transport of their merchandise. Mitsukoshi enjoyed huge status and prestige and the ordinary people of the time aspired to be able to shop there, to have a taste of the refined existence of the upper classes of the day, as encapsulated by the department store’s catch copy: ‘Enjoy the Imperial Theatre Today, Enjoy Mitsukoshi Tomorrow.’ Another example of Katayama’s innovative spirit was the first All-Japan Motor Show (now the Tokyo Motor Show), which he conceived of and promoted. It was held in 1954 with the participation of all of Japan’s automakers and helped spur the rapid advance of motorisation in the country.

Among the various milestones in Katayama’s career at Nissan during this period, one event worthy of special mention is a class victory in 1958 at the Mobilgas Trial—Round Australia, where two Datsun 210s were entered, the Fuji and the Sakura. Prior to the full-scale export of Datsun cars, the company wanted to test their performance and potential by entering them in the world’s most gruelling automobile race, covering 16,000 km of unpaved roads in the harsh Australian outback over the course of 19 days.

He recalled, ‘At the time, the Datsun 210 was powered by a 988cc OHV engine with a maximum output of 34ps. If you loaded it up with enough spare parts to handle the worst-case scenario on that route, it wasn’t much different from squishing eight people into this four-passenger car. Honestly, even though I was the team manager, I didn’t think we would win.’

Against all odds, however, the Fuji won the race in the class up to 1,000cc. News agencies around the world immediately reported this incredible achievement and the Datsun name and Datsun’s toughness were catapulted into the limelight worldwide. However, even as he received this welcome news and he and the team celebrated their famous victory, Katayama was absorbing a lesson that had struck home like a hammer blow and left him almost humiliated during the rally that circumnavigated the Australian continent.

‘The car that won the overall victory, one of our rivals, was not a sturdy car at all. In fact, it was rather weak. So how on earth could such a car have won the rally? The answer is that our rival was very well prepared to deal with any problems that arose by making the most use of its dealer network, which was established throughout Australia, and deploying service teams at every strategic point. We are talking about the cars of 55 years ago and in general they could not drive 16,000km at one go without any problems. But if you have mechanics on hand to change the oil and filters, check fluid levels, replace parts, and make adjustments and repairs as needed, then a vehicle definitely gets back to having a “healthy body”, as it were. Witnessing this, I realised that cars were the same as people. If you always have doctors and medicine standing by as needed, you can expect to get healthy again if you should happen to fall ill.’

Grateful for friendship

Spurred

by

its

success

in

the

Australian

rally,

Nissan

Motor

launched

full-scale

exports

of

Datsun

cars

and,

in

1960,

the

company

sent

Katayama

to

Los

Angeles,

which

was

the

front

line

of

the

market.

‘More

than

to

promote

the

performance

and

toughness

of

our

products,

[I

went

to

the

US]

to

build

a

service

network

that

was

capable

of

responding

to

any

problems

quickly.

The

goal

was

to

build

a

dealer

network

where

the

main

doctors

for

Datsuns

were

always

on

duty

and

spare

parts

were

always

sufficiently

stocked.’

But dealers selling new cars on the West Coast responded coldly to this strange Japanese businessman who was suddenly visiting them with an unfamiliar model. Katayama therefore got things started by calling on dealers of pre-owned cars, one by one, and asked them to become Datsun dealers.

‘In the beginning, Datsun dealers had no status or prestige and they were not wealthy either. On top of that, because automobiles were constantly evolving, parts would go out of use after six months as they were replaced by new designs. Nevertheless, I asked the dealers to make sure they were ready for any problems by stocking spare parts and they responded by saying that they understood and they worked hard to comply. During the difficult times, we all gritted our teeth and worked together and we made it through. For me, they are not just dealers but friends. I’m speaking like I’m a big man, but I owe everything to them.’

Meanwhile,

Japanese

engineers

were

visiting

the

US

in

groups

of

around

10,

with

the

aim

of

making

the

company’s

products

more

competitive

and

more

attractive.

They

visited

dealers

in

different

states

and

learned

and

absorbed

first-hand

how

Datsun

cars

were

used

in

the

US

and

what

kinds

of

vehicles

US

customers

were

looking

for.

‘In

those

days,

the

US

government

hardly

ever

issued

work

visas

to

the

Japanese.

The

only

way

to

enter

the

country

was

on

a

tourist

visa,

which

only

let

you

stay

in

the

States

for

two

weeks.

When

it

expired,

you

went

to

Canada

and

then

re-entered

the

US.

That’s

just

one

example

of

the

problems

and

difficulties

we

had

to

put

up

with.’

This groundwork was rewarded in a big way in 1967 when the company introduced the Datsun Bluebird 510, a masterful car with a clean body powered by a newly designed SOHC engine and incorporating a four-wheel independent suspension. And then, when the 510-based Z-car (240 Z in the US) was launched, the company’s US dealers found themselves welcoming throngs of people scrambling to buy a Datsun.

‘Our dealer friends, with whom we had shared the hard times, were able to grow into successful businessmen in handsome suits. But all of them were very grateful and they thanked Nissan for helping them achieve such success. Friends are blessings (laughter).’

In this way, Yutaka Katayama laid the foundations for Nissan’s explosive growth in the US. His straightforward manner and his steadfast belief in and commitment to the industry and his work won the respect and admiration of the leaders of the US auto industry and of the entire automotive community in the US, such that Katayama was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in Dearborn, Michigan in 1998. Mr K reflected the affection and expectations he had for the horses of his boyhood directly in his life and work and throughout his life he has charmed the people around him. For a car enthusiast, his life is endlessly enviable.

Writer Profile

Yoshihisa

Hayata

Born

in

1967

in

Tochigi

Prefecture.

Hayata

was

totally

swept

up

by

the

super-car

boom

when

he

was

9th

and

grew

up

with

a

love

of

cars

that

has

continued

to

this

day.

After

graduating

from

university,

he

went

to

work

for

specialist

automotive

magazines

such

as

Autosport,

Car

Graphic,

and

Navi.

He

currently

is

back

with

Car

Graphic

again.

A

46-year-old

guy

who

is

also

an

enthusiastic

fan

of

ice

hockey

team

HC

Tochigi-Nikko

Ice

Bucks.